پرفروشترین

پرفروشترین، محبوبترین محصولات

انگشتر طلاروس-انگشتر مردانه-انگشتر نگین مشکی-انگشتر رنگ ثابت-هدایای ماندگار-هدیه ماندنی-نیم ست طلایی-نیم ست نقره ای-گوشواره گردنبند-نیم ست استیل-هدیه روز زن-هدیه روز دختر-هدیه روز پرستار-هدیه روز معلم-هدیه روز مادر-هدیه ولنتاین-نیم ست مشکی-نیم ست هولوگرامی-حلقه استیل-حلقه نامزدی-رینگ استیل-رینگ نامزدی-رینگ جفتی-حلقه جفتی-حلقه ولنتاین-حلقه ساده-حلقه ست-حلقه مردانه-حلقه زنانه-حلقه کلاسیک-حلقه کارتیه-حلقه فشن-حلقه سیاه قلم-حلقه رویال-حلقه رنگ ثابت-حلقه دورنگ-حلقه پسرانه-هدیه سپندارمذگان-هدیه روزعشق-گردنبند کارتیه-گردنبند مردانه-گردنبند فیگارو-زنجیر مردانه-زنجیر کارتیه-برس انگشتی-برس پلاستیکی-برس جیبی-برس اتمی-برس کف دستی-برس حمام-برس مسافرتی-برس تاشو-انگشتر دیزاینر-انگشتر استیل-انگشتر طرحدار-انگشتر بدون نگین-زنجیر استیل-زنجیر طلایی-زنجیر نقره ای-زنجیر کبریتی-زنجیر اسپرت-جاکلیدی ذره بین-جاکلیدی بزرگ نما-جاکلیدی کاربردی-جاکلیدی ابزاری-زنجیر گردنبند-زنجیر رنگ ثابت-زنجیر دیپلمات-

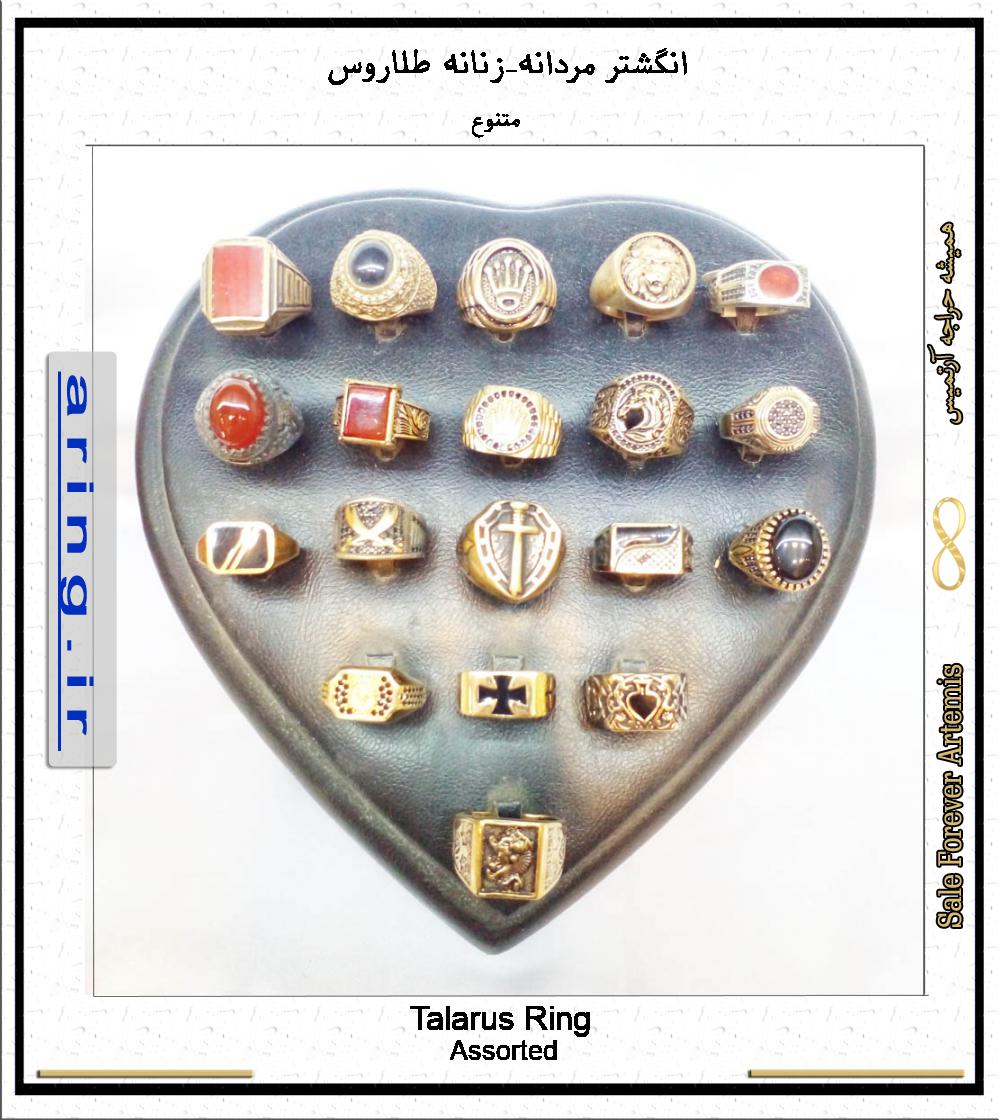

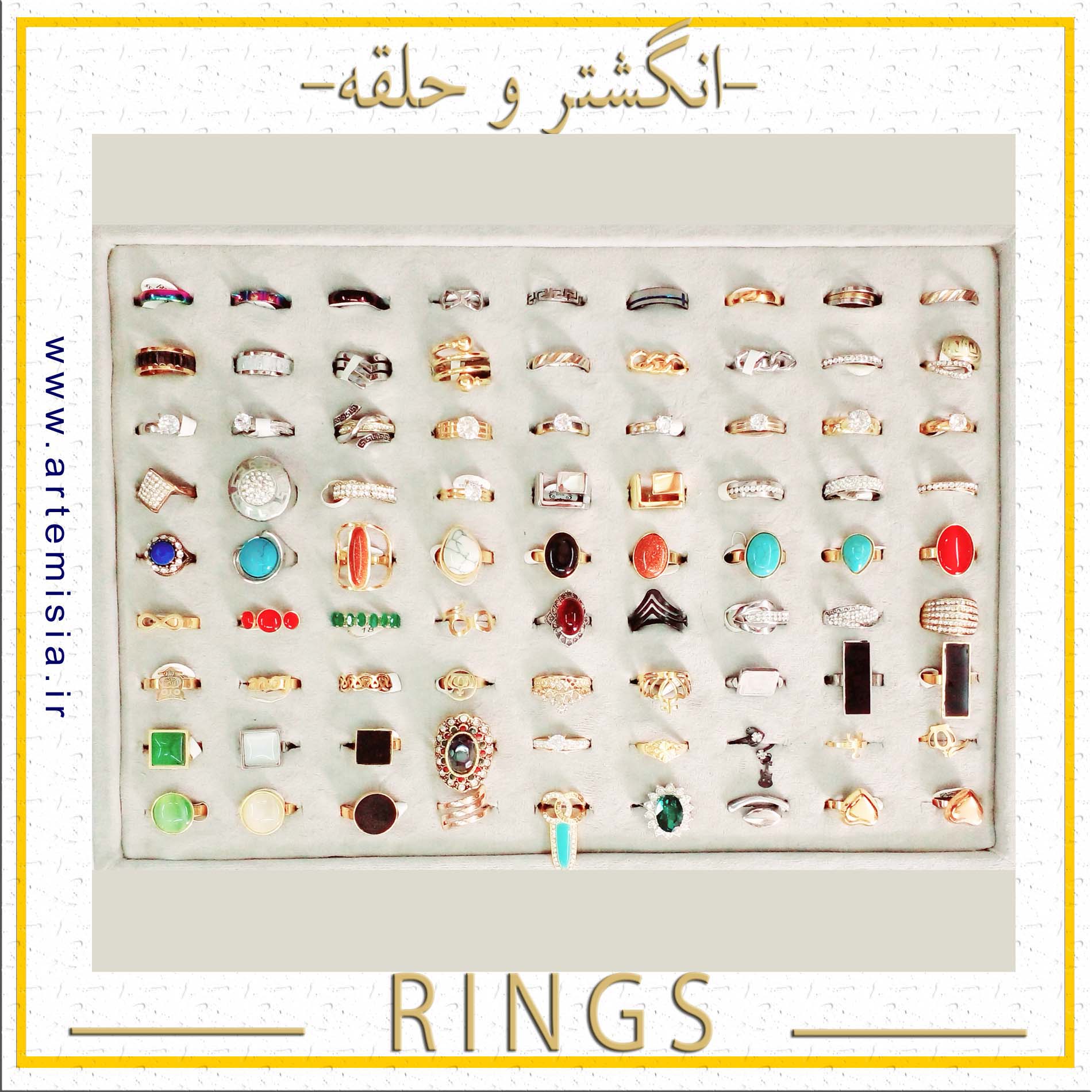

انگشتر مردانه-زنانه طلاروس متنوع

55000 تومان

انگشتر طلاروس آرتمیس پدیده ای جالب در صنایع بدلیجات است که به خاطردوام فوق العاده بالا طرفداران زیاد...

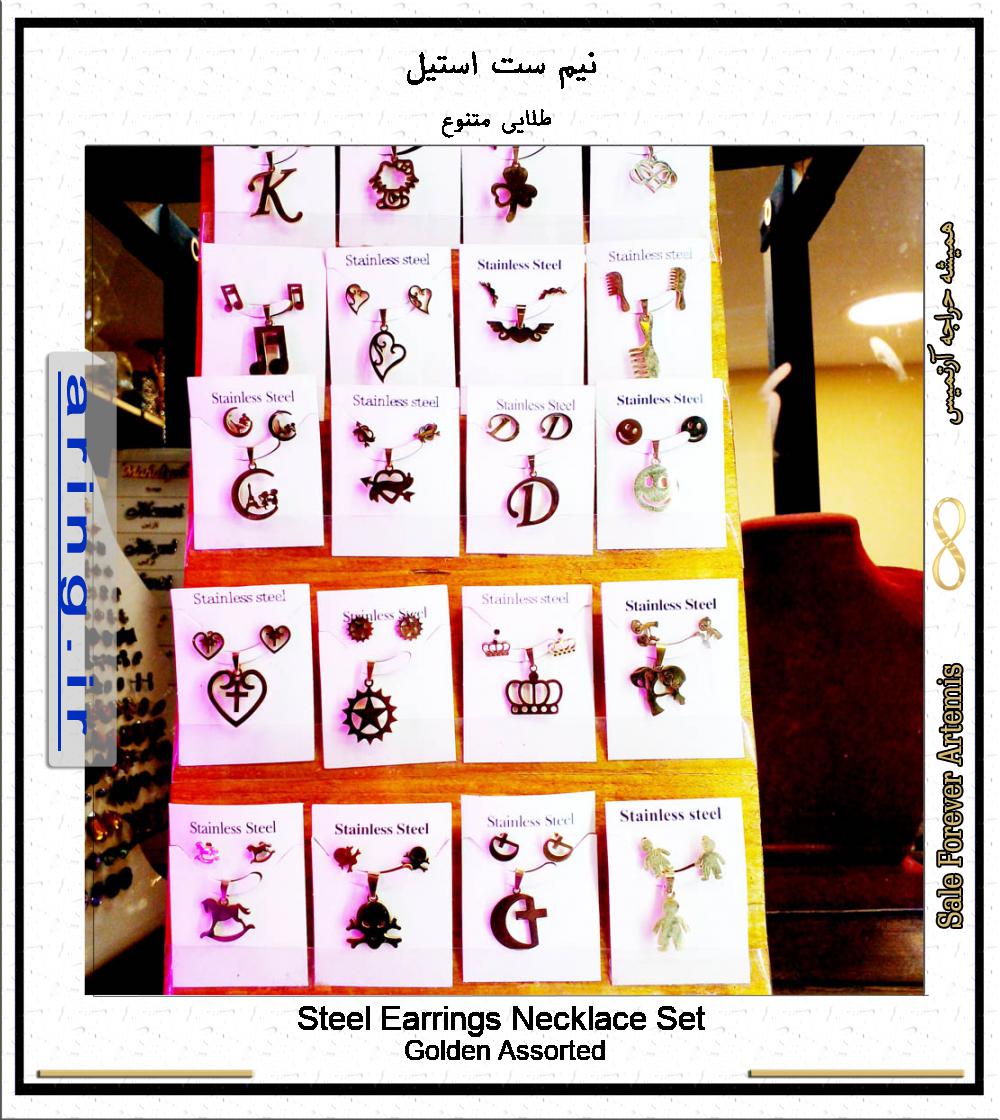

نیم ست استیل

30000 تومان

فروش ویژه نیم ست استیل با زنجیر کاملا رنگ ثابت و ضد حساسیت. نیم ستهای آرتمیس شامل یک جفت گوشواره پین...

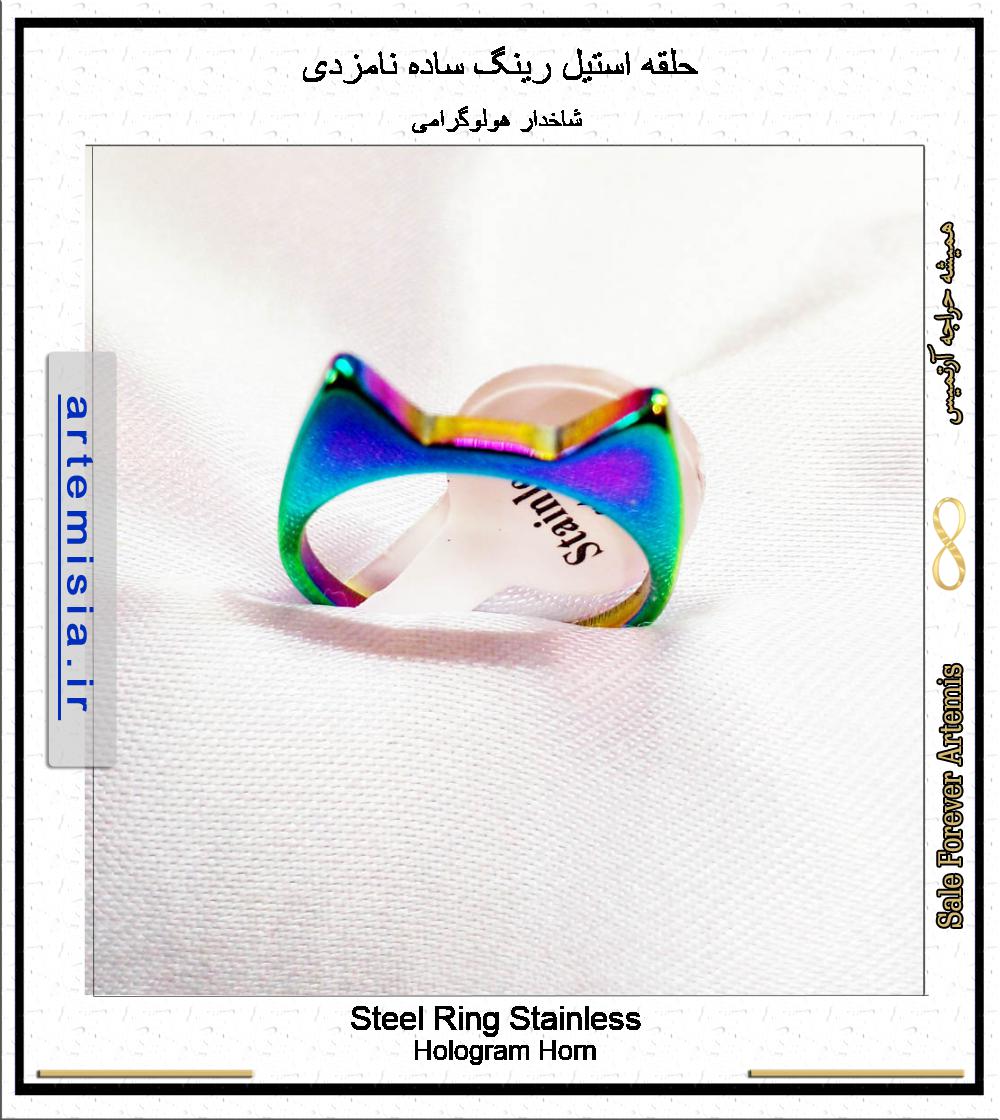

حلقه استیل رینگ متنوع نامزدی

20000 تومان

حلقه استیل با اینکه طلا نیست ولی انگشتری رنگ ثابت است و ماندگاری بالایی دارد. حلقه استیل رینگ ساده ن...

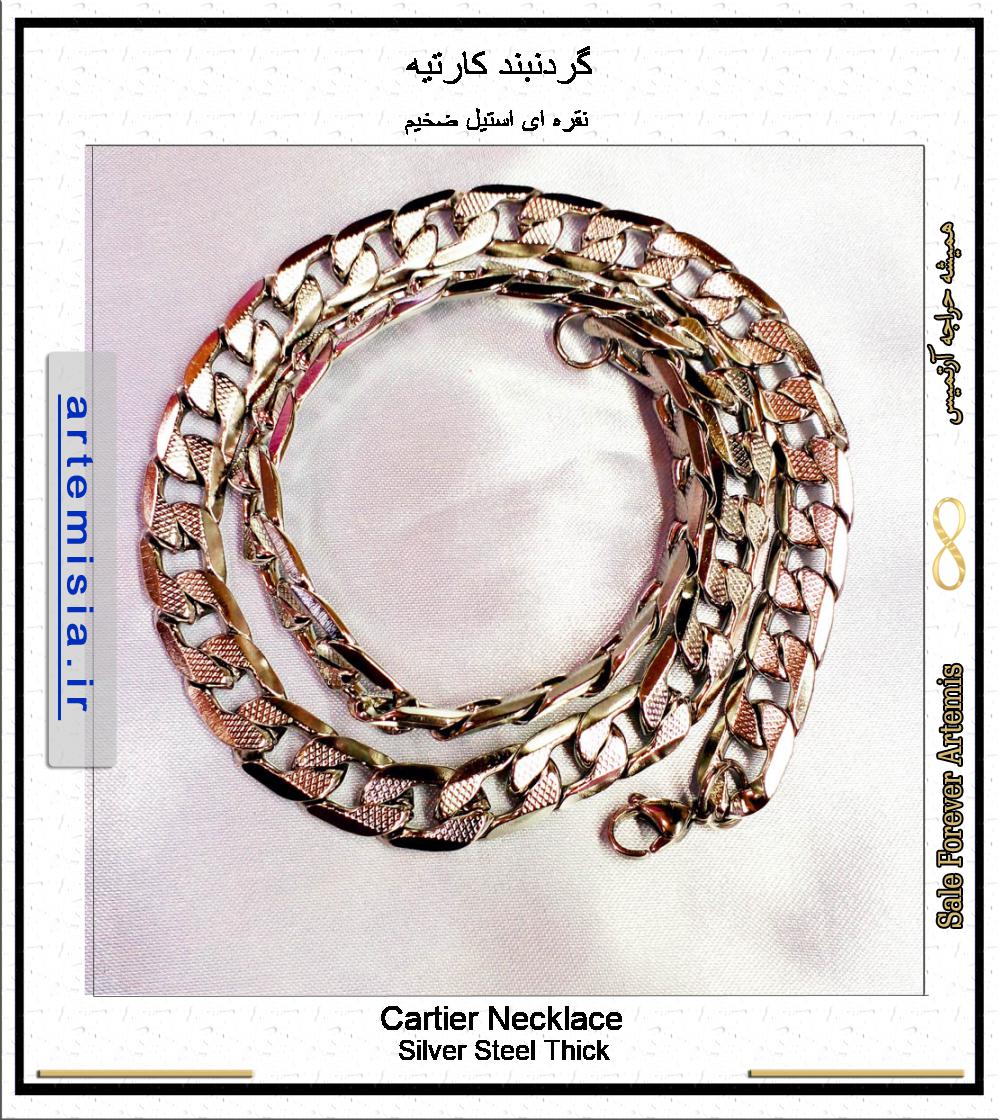

گردنبند کارتیه

60000 تومان

گردنبند زنجیر استیل کارتیه Cartier (در بازار موسوم به کارتیر) در مدلهای فیگارو.... نوعی زنجیر زیبا، ...

برس انگشتی جیبی پلاستیکی

4000 تومان

برس انگشتی نوعی برس پلاستیکی ساده است که به برس جیبی, برس اتمی و برس کف دستی نیز معروف است. وسیله ا...

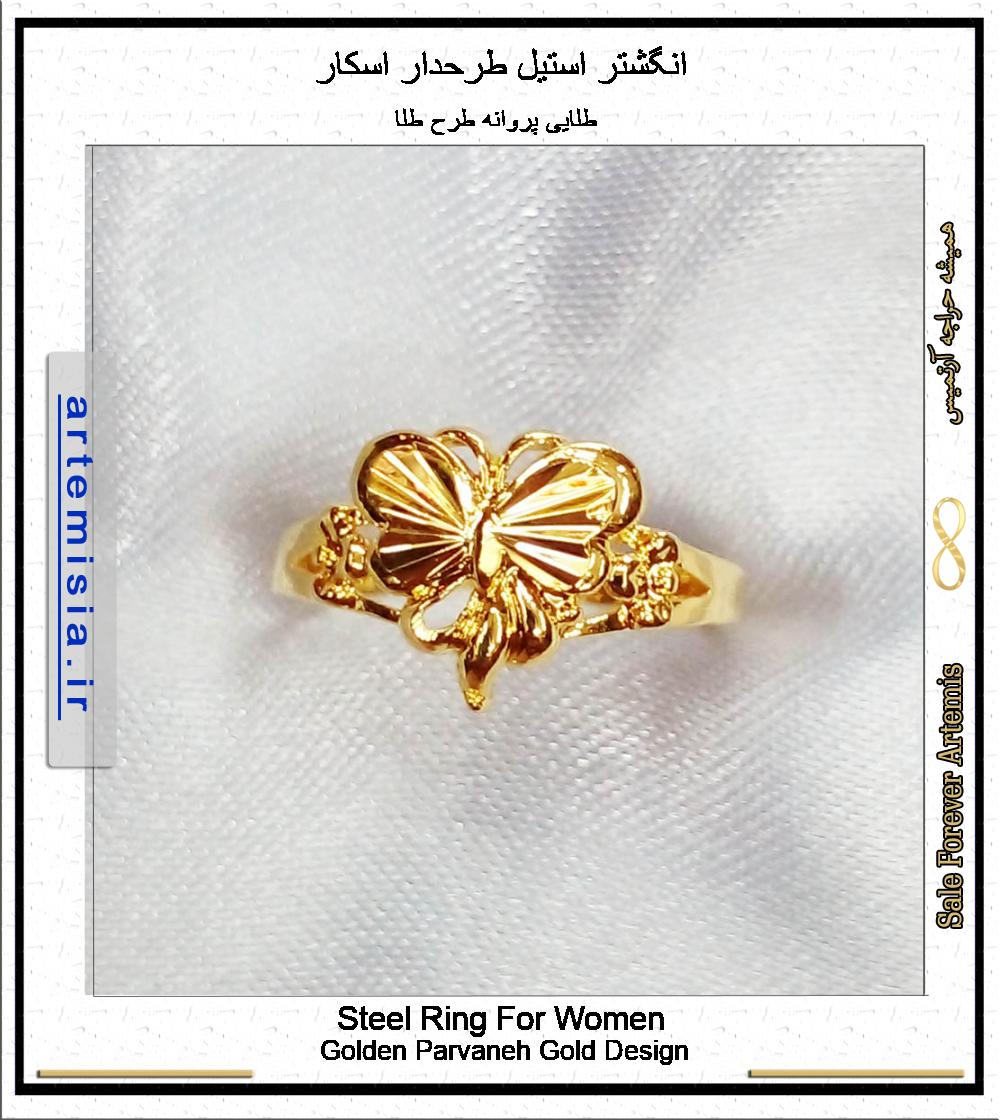

انگشتر استیل طرحدار اسکار

50000 تومان

انگشتر اسپرت آرتمیس از جنس استیل در طرحهای متنوع (ضربان، قلب، تاج، بینهایت و ...) رنگ ثابت طلایی و ن...

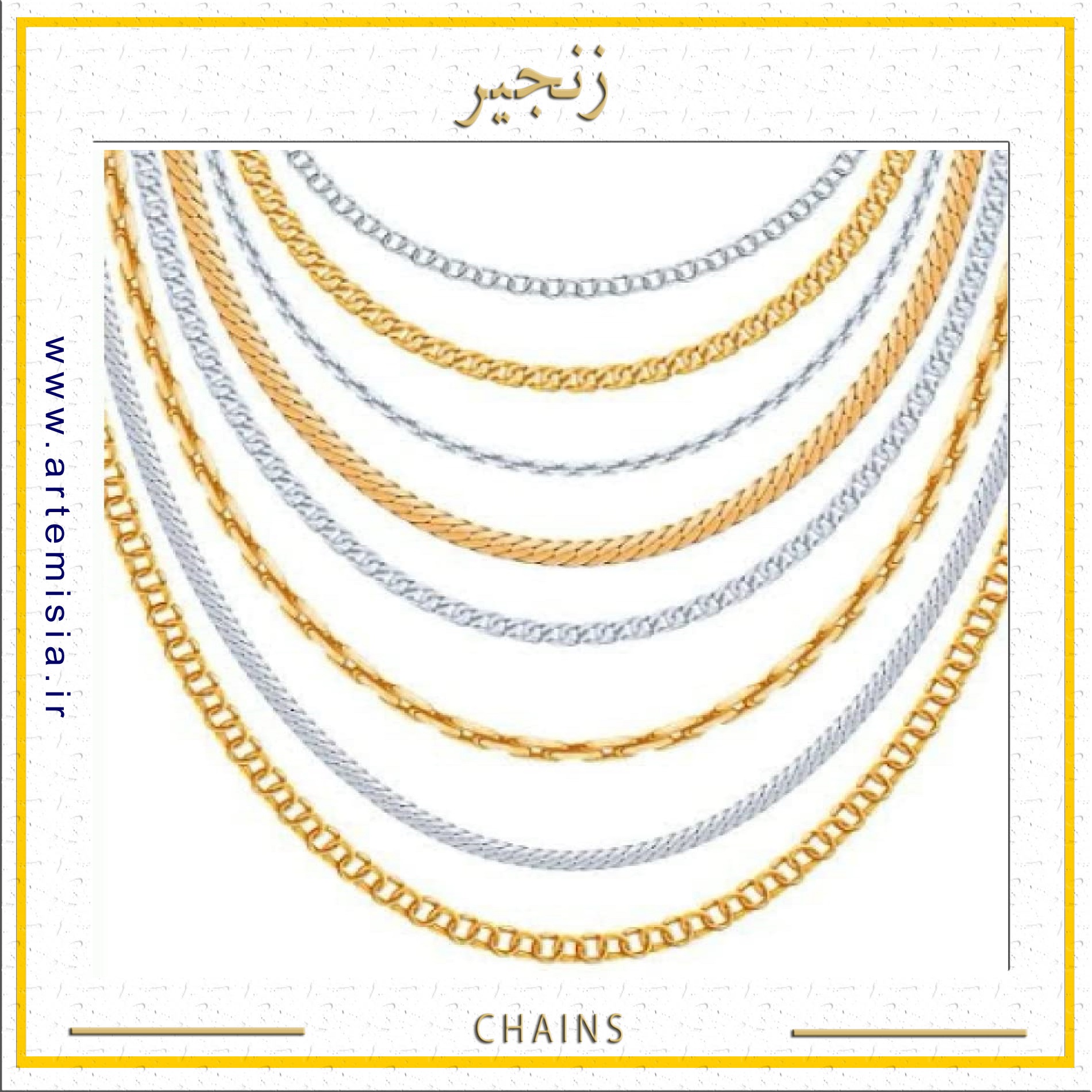

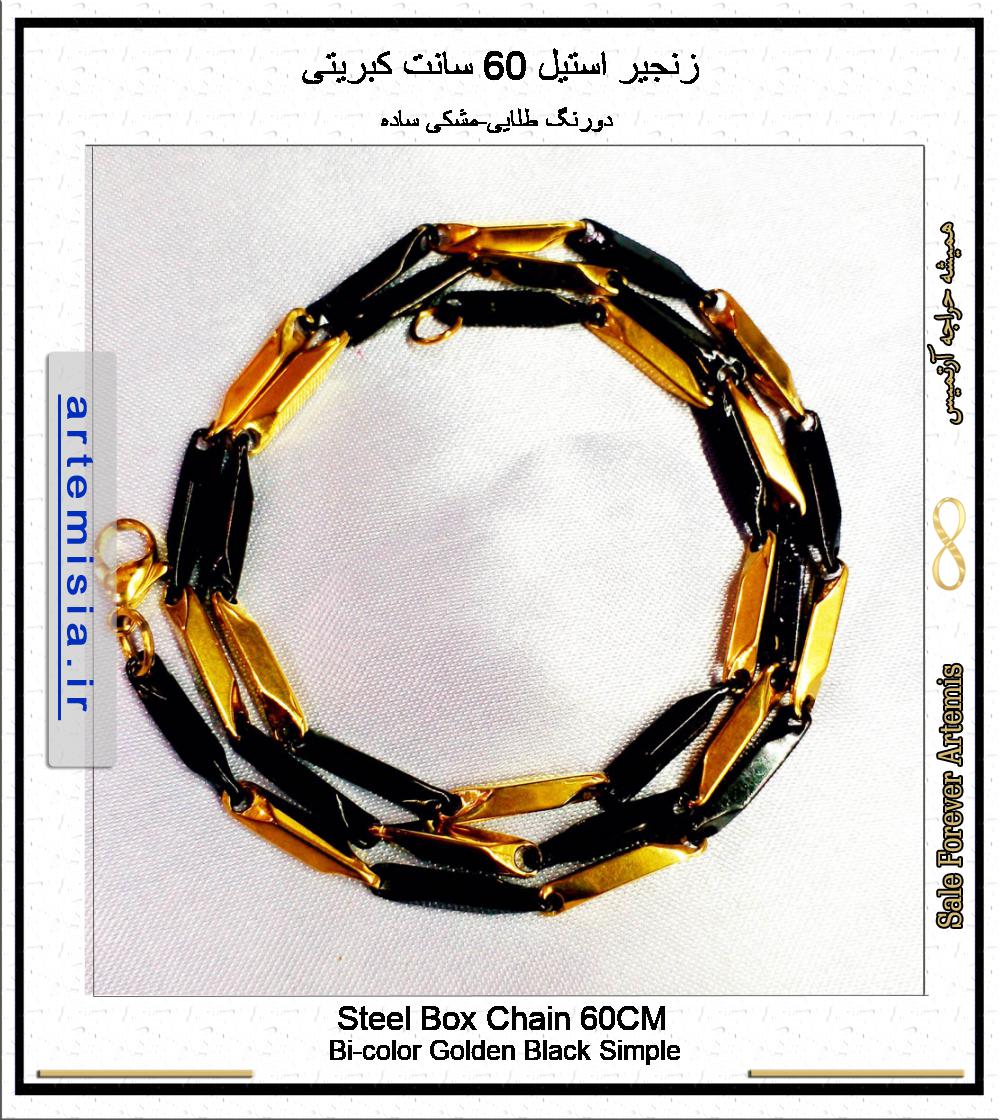

زنجیر استیل 60 سانت کبریتی

100000 تومان

زنجیر گردنی استیل اسپرت 60 سانت کبریتی در رنگهای طلایی، نقره ای، و دورنگ » بسیار شیک و با دوام. رنگ ...

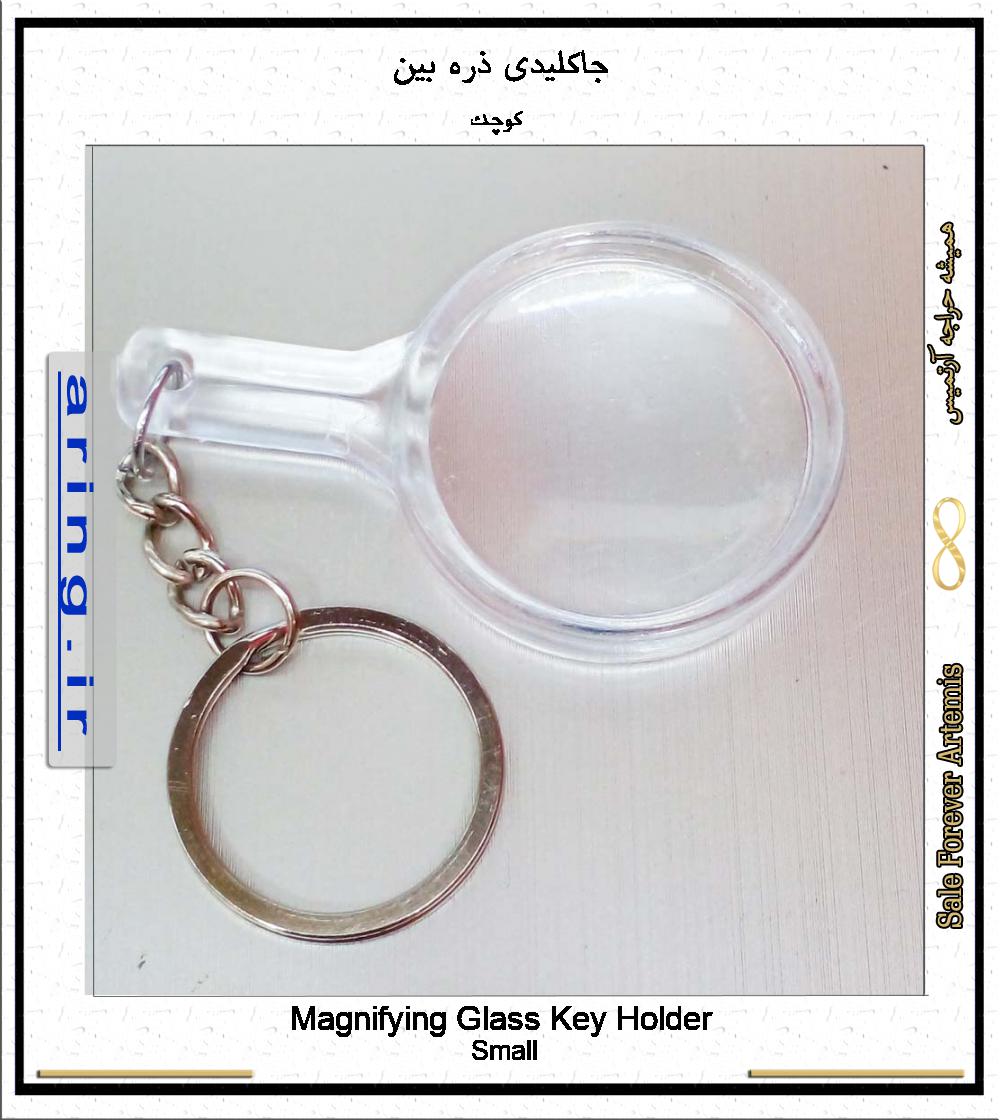

جاکلیدی ذره بین

15000 تومان

جاکلیدی ذره بین دار جزو ابزارهای مورد نیاز برای افراد مسن و اشخاصی که ضعف بینایی دارند ویا نزدیکبین ...

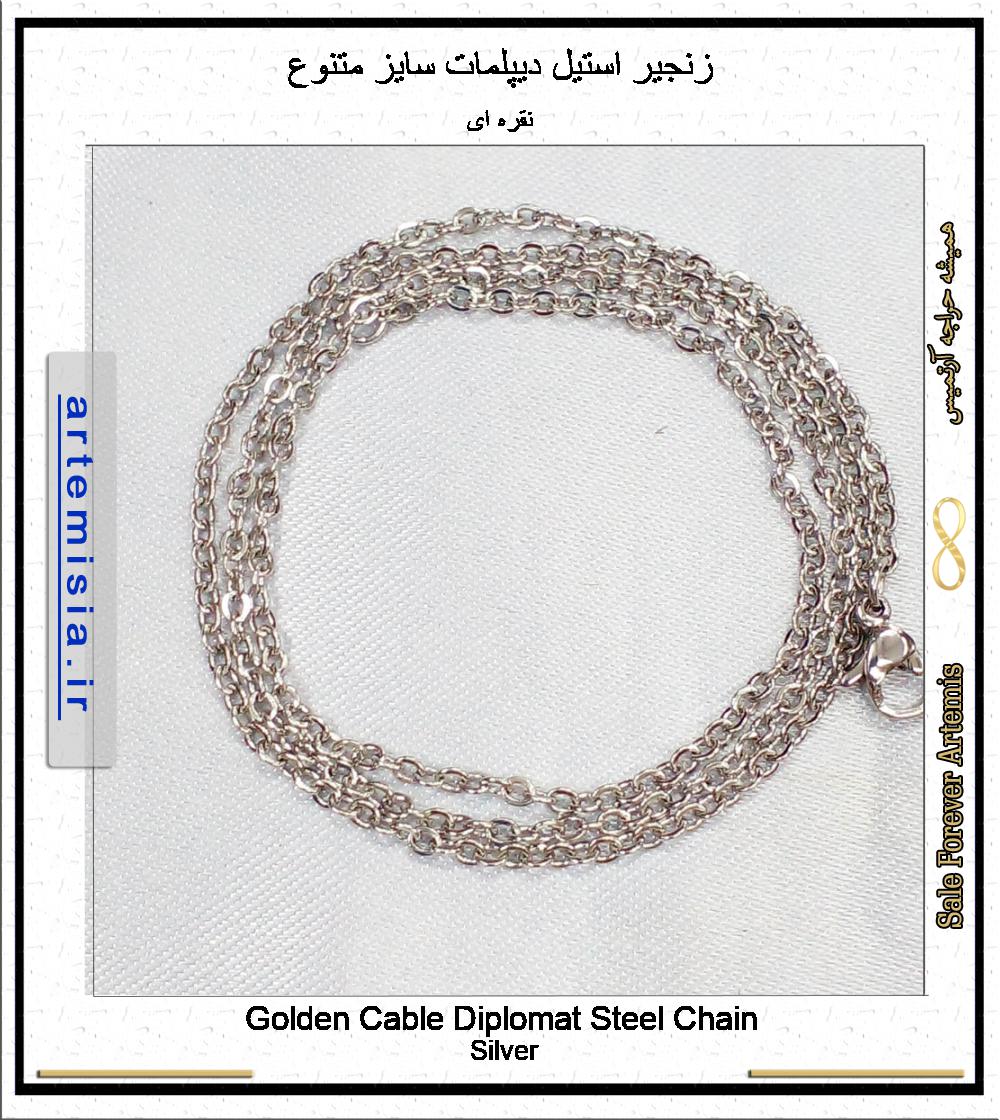

زنجیر استیل دیپلمات سایز متنوع

20000 تومان

زنجیر استیل دیپلمات از 35 سانت تا 75 سانت برازنده شیک پوشان: کیفیت عالی استیل رنگ ثابت بسیار درخشان ...

پرطرفدارترین گروه کالاها

انگشتر

انگشتر استیل,انگشتر فری سایز,انگشتر اسم انگلیسی,انگشتر اسم لاتین,انگشتر اسم فارسی,دستبند اسم لاتین,دستبند اسم انگلیسی

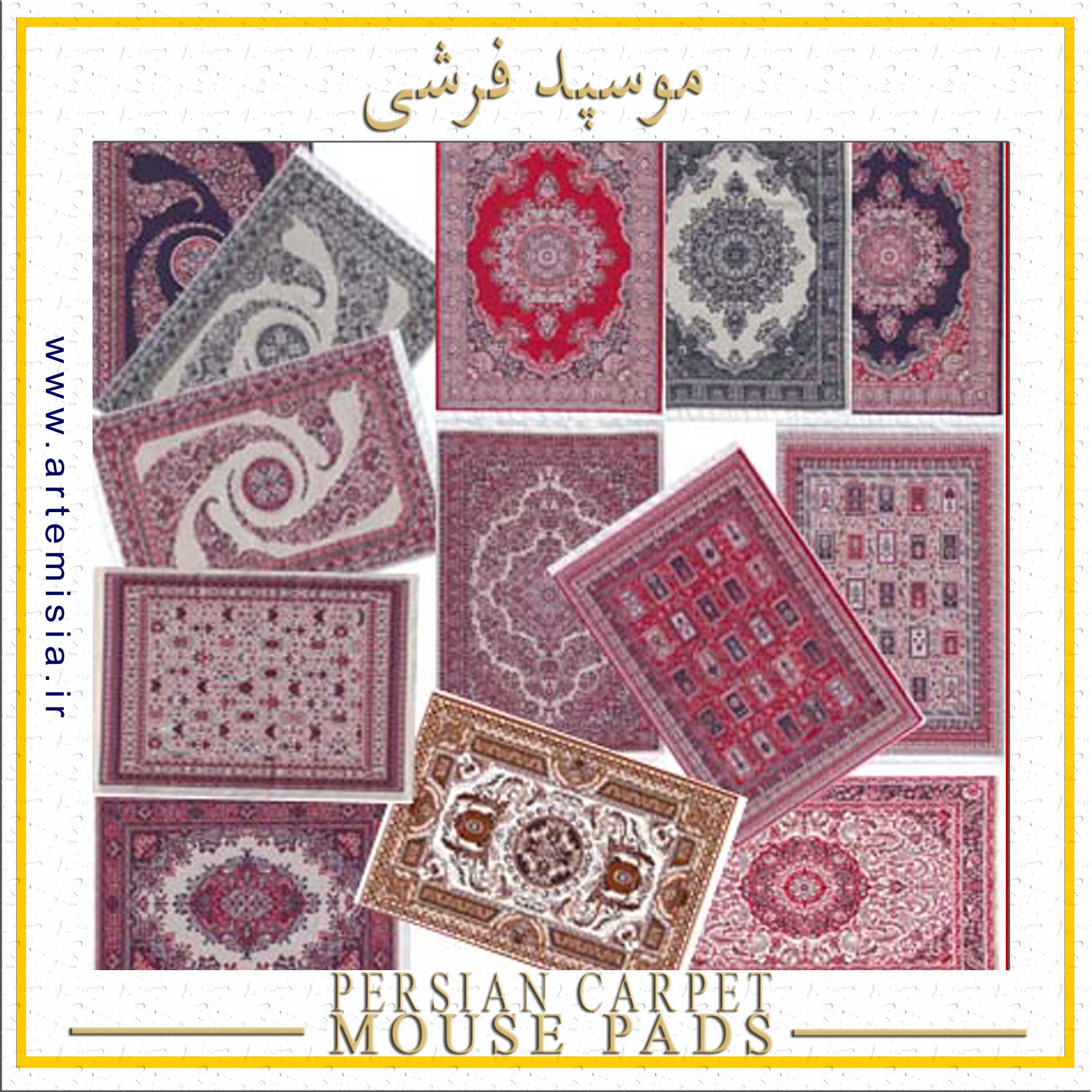

پدموس فرشی

سوغات ایران,موسپد قالی ایرانی,موسپد فرشی سنتی,موس پد قالی,موس پد فرش ایرانی,زیر موسی فرشی,طرح قالی ایرانی

ست و نیم ست

نیم ست استیل,نیم ست رنگ ثابت,گردنبند رنگ ثابت,نیم ست طلایی,هدیه روز دختر,نیم ست نقره ای,گوشواره رزین

ابرهشتگ

←آویز دستبند←آویز فلزی←آویز گردنبند←استیل←اسی←انگشتر←انگشتر استیل←انگشتر اسم انگلیسی←انگشتر اسم فارسی←انگشتر اسم لاتین←انگشتر رنگ ثابت←انگشتر فری سایز←انگشتر گل←ایران←ایرانی←بزرگ←تاج←تحریر طلایی←ترانه←ترمه←تندیس←جاکلیدی←حلقه←خرج دستبند←خرج گردنبند←دست←دستبند←دستبند استیل← دستبند مروارید←دستبند کشی←دی←رایجترین اسامی←رایجترین نامها←روسری←زنجیر←زیبا←زیبا ترین اسامی←سامی←سایز انگشتر←طرح فرش←طلا←طلایی←طلایی نگیندار←فارسی طلایی←فارسی نقره ای←فلزی←لاتین طلایی←لاتین نقره ای←ماوس پد فرشی سنتی←متوسط←مجبوبترین اسامی←مجبوبترین نامها←مروارید←معمولی←موس پد طرح گلیم←موس پد فرشی←ندا←نقره ای←نقره ای نگیندار←نگین←نگیندار←هدیه←پر←پلاک←پلاک آویز←پلاک اسامی←پلاک اسامی استیل←پلاک اسامی فارسی←پلاک استیل←پلاک اسم←پلاک اسم ایران←پلاک اسم ترانه←پلاک اسم زیبا←پلاک اسم سامی←پلاک اسم ندا←پلاک اسم نگین←پلاک تاج←پلاک تندیس←پلاک دستبند←پلاک دستبند دست←پلاک رنگ ثابت←پلاک طلایی←پلاک نت←پلاک نگیندار←پلاک گردنبند←کش دستبند←کش مو←کوچک←کیف←کیف زنانه←کیف پول←گالری تندیس و پلاک←گردنبند←گردنبند اسم←گردنبند اسم زیبا←گردنبند اسم سامی←گردنبند نام←گل←گل مو←گوشواره

همیشه حراجه آرتمیس فقط شعار نیست!

- کلیه اطلاعات کاربری محفوظ است

- ارسال پستی در ایران

- جهت اطمینان از موجودی، تخفیف عمده، نمایندگی ،لطفا تماس بگیرید

https://danamotor.ir/media/GRP58_Top_Seller.jpg

لینک: http://parseed.ir/?linkid=20430&qlang=en

اطلاعات تماس

آرتمیس-ایران

- فروشگاه آرتمیس

بازار تهران - خ 15 خرداد - پ 560 روبروی پامنار - پاساژ گالریا طبقه منفی 1

021-55583681-82

حتما قبل از مراجعه حضوری تماس بگیرید

آرتمیسیا امور نمایندگی-فروش عمده : 09227489149 - 09337879149 - شعبه کیلان: رشت - کمربندی بهشتی نبش کوچه پژمان تلفن : 09209792294

- ایمیل: mimahoda@gmail.com